- Finding Unshakable Power in a World That Wants to Pull Us ApartPosted 5 months ago

- What could a Donald Trump presidency mean for abortion rights?Posted 5 months ago

- Financial Empowerment: The Game-Changer for Women in Relationships and BeyondPosted 6 months ago

- Mental Health and Wellbeing Tips During and After PregnancyPosted 6 months ago

- Fall Renewal: Step outside your Comfort Zone & Experience Vibrant ChangePosted 7 months ago

- Women Entrepreneurs Need Support SystemsPosted 7 months ago

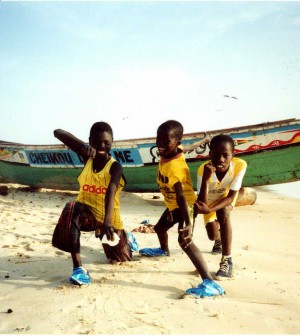

Senegal - Peaceful, Democratic, But Where Are Women's, Children's Rights?

Author: Misha Hussain ~ Thomas Reuter Foundation http://www.trust.org

Senegal, one of the few African countries that has not had a major civil conflict or coup, is often held up as an example of good governance in the region – a good place for the cultural summit of French-speaking nations held in Dakar last weekend.

However, a closer look at the government’s policies in the four decades since independence from France in 1960 shows that peace and prosperity haven’t necessarily been used to ensure women’s and children’s rights on the ground.

The francophone summit this year focused on women and youth – an area where Senegal has made little headway in the fight against female genital mutilation (FGM), little progress in tackling child marriage or early pregnancies and upholds a legal ban on abortion.

The International Federation of Human Rights released a report to coincide with the summit saying that the country’s draconian abortion legislation forces some unmarried mothers to kill their infants, or risk ostracisation.

Amy Sakho, a counsellor for the Senegalese Association of Women Jurists, a legal aid group that runs drop-in centres for women in Dakar, told me girls as young as nine years old had been refused abortions, even after rape. In one such case, the girl died two months later.

In contrast Cape Verde, a regional leader in good governance according to the Mo Ibrahim Index, allows abortion without restrictions. Most west African nations allow abortion to preserve a woman’s physical or mental health, and certainly to save a women’s life.

As a parent myself, it grieves me to see Senegalese women pushed to such extremes by Napoleonic laws that have not been changed since the early 19th century, even though other laws from the same period have evolved, permitting family planning.

As a parent myself, it grieves me to see Senegalese women pushed to such extremes by Napoleonic laws that have not been changed since the early 19th century, even though other laws from the same period have evolved, permitting family planning.

Many point the finger at the Muslim brotherhoods, four powerful religious groups which have a strong presence in key decision making areas and exert influence to make sure these conservative principles remain in place. Ninety-four percent of Senegalese are Muslims.

Child marriage and early pregnancy is another sticking point for Senegal, as government data show that around 25 percent of girls between 15 and 19 are married, rising to 36 percent in rural areas and 52 percent in the poorest parts of the country.

Likewise, 16 percent of 15- to 19-year-olds already have a child, increasing to 20 percent in rural areas and 31 percent in the poorest regions, according to the U.S.-based Guttmacher Institute, which works on reproductive health.

The low budget film, “Tall as the Baobab Tree“, shows how poverty and lack of education drive families to give away their girls at such a young age. The film also shows how the religious leaders play a crucial role in making such decisions.

The same religious and traditional influences have prevented the government from reaching its target of ending FGM by 2015, despite the millions of dollars of aid money ploughed into charities to empower women and communities through education.

According to a UNICEF report in 2013, 18 percent of women aged 45-49 believed FGM should continue, compared with 16 percent of girls aged 15-19 – only a slight difference between the generations. Clearly, attitudes have not changed much.

The late Efua Dorkenoo, a world leader in the campaign to end FGM, who died in October, told me in an interview in February that education alone would not end FGM – the perpetrators must be put behind bars.

In neighbouring Burkina Faso, which has a similar religious and traditional heritage, better law enforcement, hotlines for girls in danger and safe houses where they can seek shelter have dramatically reduced the number of FGM cases.

Dorkenoo said it was too easy to blame religious and traditional beliefs, which are often a convenient excuse for inaction. In reality, where there is a will to stop violence against women, there is a way.

Take for example the progress Senegal has made in contraceptive use, which has jumped from 12 percent in 2010 to 16 percent in 2012, according to the latest national health surveys.

Unfortunately, the good news stops there. It’s time for Senegal to find a way.